As usual, in the days before Christmas I somehow ended up watching a re-re-repeat of a Santa Claus movie. The very western, consumerist, stereotypical, nonsensical plot, complete with Rudolph and elves, is of course hogwash. Nevertheless, it worked its magic on me once again, immersing me in its fundamental message – it is okay to believe in magic, even when you know darn well that it isn’t real. And the reason it is okay to do this is because we are human beings; we need to have stories of magic which survive the test of time and logic, because at their very core they embody fundamental norms which underpin a healthy society. It is doubtful whether researchers practicing scientism understand this.

Scientism is the practice where science is employed selectively in order to attack humanistic thought and ideals. It is the stance which posits that science is always right and everything else is dogma, and it always accompanies an entirely objective view of reality which denies the primacy of subjective existence in other people’s lives. It helped give us nazism, communism, DTT, thalidomide, eugenics, nuclear weapons, and so on. The practice of scientism often attracts researchers who see advantage in positioning themselves within prevailing ideologies in order to gain funding and prestige. To this end, these individuals are adept in representing discoveries and findings in ways that re-enforce prevailing ideologies and trends; most seem to do this unconsciously, almost in an instinctive manner - no doubt because of processes inherent in their training and other socialising factors. In this, paradoxically, they end up being some of the most subjective individuals around.

Reading the latest story on homosexuality over at The Conversation website demonstrated for me once again how the politicisation of science is a means through which the fundamental structure of the good society is being undermined. The story, titled New ideas about the evolution of homosexuality, is written by an evolutionary ecologist, Rob Brooks. In it, Brooks discusses a recent paper which models the possible effect of epigenesis on homosexuality, and then supposes that this illuminates why homosexuals might feel that they are ‘born that way’, even though no genetic evidence for this has been discovered thus far.

The first thing that strikes the reader is the political angle put on some great and exciting science. From the outset we are left in no doubt that the Conversation article is scientism, rather than merely explanation of a mathematical model developed to expand and test anew epigenetic insights on what might lead to homosexuality. This is discernible in the very first ‘fact’ presented to us (actually, it is labelled a ‘very real’ fact), which is that a “large proportion of people across the world are sexually attracted to members of the same biological sex”. How 2 to 4% of the population represents a ‘large proportion’ of the global population is not explained. Because this is a scientist's interpretation we’re talking about here, we would expect it to be more precise in how facts are presented. That this is not done highlights the politcising of the topic, it departs from a scientific discussion.

Moreover, even for a reasonably careful reader it should become apparent that the innovative use of ‘facts’ is not accidental, but something that sits within a creative approach to representing scientific findings and explanations just so that they lead to particular conclusions. Take for example the explanation for the process involving genes and epigenesis, which Brook offers his readers. It compares these through a metaphorical reference to a recipe book; not just any book, but the fictional Advanced potion making by Libatus Borage, borrowed from the popular Harry Potter stories.

Needless to say, I couldn’t really understand what the crap Brooks' really talking about. I am not a biologist, let alone an evolutionary ecologist, and so I decided to brush up on my understanding of genetics and do some research of my own. Fortunately, there are some very accessible explanations for epigenetics available; here’s one I like for its clarity:

Reading the latest story on homosexuality over at The Conversation website demonstrated for me once again how the politicisation of science is a means through which the fundamental structure of the good society is being undermined. The story, titled New ideas about the evolution of homosexuality, is written by an evolutionary ecologist, Rob Brooks. In it, Brooks discusses a recent paper which models the possible effect of epigenesis on homosexuality, and then supposes that this illuminates why homosexuals might feel that they are ‘born that way’, even though no genetic evidence for this has been discovered thus far.

The first thing that strikes the reader is the political angle put on some great and exciting science. From the outset we are left in no doubt that the Conversation article is scientism, rather than merely explanation of a mathematical model developed to expand and test anew epigenetic insights on what might lead to homosexuality. This is discernible in the very first ‘fact’ presented to us (actually, it is labelled a ‘very real’ fact), which is that a “large proportion of people across the world are sexually attracted to members of the same biological sex”. How 2 to 4% of the population represents a ‘large proportion’ of the global population is not explained. Because this is a scientist's interpretation we’re talking about here, we would expect it to be more precise in how facts are presented. That this is not done highlights the politcising of the topic, it departs from a scientific discussion.

Moreover, even for a reasonably careful reader it should become apparent that the innovative use of ‘facts’ is not accidental, but something that sits within a creative approach to representing scientific findings and explanations just so that they lead to particular conclusions. Take for example the explanation for the process involving genes and epigenesis, which Brook offers his readers. It compares these through a metaphorical reference to a recipe book; not just any book, but the fictional Advanced potion making by Libatus Borage, borrowed from the popular Harry Potter stories.

Needless to say, I couldn’t really understand what the crap Brooks' really talking about. I am not a biologist, let alone an evolutionary ecologist, and so I decided to brush up on my understanding of genetics and do some research of my own. Fortunately, there are some very accessible explanations for epigenetics available; here’s one I like for its clarity:

Epi-marks constitute an extra layer of information attached to our genes' backbones that regulates their expression. While genes hold the instructions, epi-marks direct how those instructions are carried out – when, where and how much a gene is expressed during development. Epi-marks are usually created each generation, but they contend that sometimes there is carryover between generations and that can contribute to similarity among relatives, resembling the effect of shared genes (Source: Science 2. Blog)

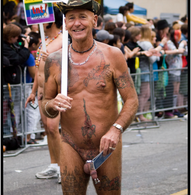

Homosexuals in full evolutionary flight

In reading alternative explanations, I realised why I couldn’t quite understand the metaphor employed in Brooks' paper. It takes an expert who is not restrained by external drivers to articulate an unambiguous explanation of the science to provide just the simple scientific/objective facts. When one tries to prevent audiences arriving at certain possible conclusions or logical deductions from one's explanations of objective facts, such explanations can become quite contorted and so are naturally hard to follow.

Judge for yourself - here's a scientific explanation on genetics, which simply outlines what the scientific knowledge on the topic is, without telling us what it should mean for important moral issues under discussion and debate in the community. Note the clear and unambiguous narrative. Here is another reference, this time to a paper explaining epigenesis, which I draw on quite a bit to inform this piece. Written by an eminent scientist and appearing in a scientific magazine, the article makes more sense than Brooks' which was written for an online publication that is meant to be accessible to non-scientists. In these pieces, please note the clarity, and the absence of references to allegorical nonsense, like recipe books for magic potions.

Nevertheless, doing the background research, I struggled with some (necessarily so) dense scientific reports. It was worth it though because I learned that Brooks exaggerates the novelty of the paper he discusses. Similar work, though with reference to different models, has been undertaken in previous studies - see for instance McNight, J. (1997) Homosexuality, Evolution and Adaption. The paper which Brooks discusses is hardly paradigmatic, and it does not provide a possible explanation for gender differences; instead it implies what most of us know intuitively and from historical wisdom, which is that homosexuality cannot be explained as some sort of desirable and normal state, but as a disorder or mutation. It is an example of how evolutionary processes lead to ‘dead ends’. The possible explanations sourced by Brooks are selective and care is taken not to touch on the very real possibility that the epigenetics trends under discussion might actually lead to mutations without evolutionary value. Propositions such as that homosexuals “provide exceptional help to their heterosexual relatives who are raising families” are comical, since I am quite certain that no one seriously envisions homosexuals as helping with the family’s chores just so that more of their nieces and nephews can carry particular genes, as the article suggests. I think that most of us visualise homosexuals in more realistic environments, such as public bath houses, certain parks in your local town, or gay bars. There is ample research which informs about the outcomes of homosexuality, which appear to have little to do with adaptation and survival of human beings, and more to do with high risk behaviours, self-harm, harm to others - from a natural selection perspective, these are hardly desirable traits .

Personally, as I begin to understand it (albeit still in very basic terms), I find epigenetics to be exciting, because it explains the relationship between the DNA, its function in replicating life and particular characteristics, and the effects of environmental factors on this function. It’s also elegant; epigenesis involves what biologists refer to as ‘gene transcription’, which choreographs complex chemical interactions (e.g., methylation) at molecular level to determine biological outcomes without changes to the DNA.

Somewhere I’ve read a nice analogy, likening the DNA/genes and epigenesis to computer hardware and software, respectively. So DNA/genes are like the hardware – the computer. However, the computer cannot function without software; it needs an ‘operating system’. The DNA is like the hardware, whilst epigenesis is like the software . Epigenesis makes the genes function as instructed by the code inherent in the DNA … most of the time. Sometimes, however, you get a computer which does not function as intended. This was certainly true for me yesterday, when my PC at work would not read any of the USB sticks I stuck into it. I rung the IT people and, in true IT Crowd style, they took me through the ‘noob’ detection steps: 'turn the PC off and on; try the USB sticks in a colleague’s PC; check that you have the latest updates for Windows' ...

So where am I going with this? Well, I don’t need to be an IT person to understand that the PC was not functioning as intended. The IT Crowd at my work (I love them, actually, they’re so true to type, and fantastic people to boot) didn’t simply say “it’s normal, so get over it and accept it” – they came and fixed it.

Obviously, I am not saying that homosexuality should be ‘fixed’ in a similar manner as a computer might be fixed. I am certainly not in favour of electrocuting or sticking ice picks into people's frontal lobes to re-program them, whether they're manic depressive, homosexual, schizophrenics/shamans or witches. However, nothing takes away from the simple fact that, as I understand it, epigenesis is part of that genetic function which replicates life, and so it is part of the process that selectively employs genetic traits in a continuous drive to enhance the species' chances of adaptation and survival across generations. My understanding is that any other outcome is outside this blind function. Here is a somewhat lengthier quote, which merits close reading because it offers a clearer explanation of how certain traits can persist (bold type is for emphasis):

Judge for yourself - here's a scientific explanation on genetics, which simply outlines what the scientific knowledge on the topic is, without telling us what it should mean for important moral issues under discussion and debate in the community. Note the clear and unambiguous narrative. Here is another reference, this time to a paper explaining epigenesis, which I draw on quite a bit to inform this piece. Written by an eminent scientist and appearing in a scientific magazine, the article makes more sense than Brooks' which was written for an online publication that is meant to be accessible to non-scientists. In these pieces, please note the clarity, and the absence of references to allegorical nonsense, like recipe books for magic potions.

Nevertheless, doing the background research, I struggled with some (necessarily so) dense scientific reports. It was worth it though because I learned that Brooks exaggerates the novelty of the paper he discusses. Similar work, though with reference to different models, has been undertaken in previous studies - see for instance McNight, J. (1997) Homosexuality, Evolution and Adaption. The paper which Brooks discusses is hardly paradigmatic, and it does not provide a possible explanation for gender differences; instead it implies what most of us know intuitively and from historical wisdom, which is that homosexuality cannot be explained as some sort of desirable and normal state, but as a disorder or mutation. It is an example of how evolutionary processes lead to ‘dead ends’. The possible explanations sourced by Brooks are selective and care is taken not to touch on the very real possibility that the epigenetics trends under discussion might actually lead to mutations without evolutionary value. Propositions such as that homosexuals “provide exceptional help to their heterosexual relatives who are raising families” are comical, since I am quite certain that no one seriously envisions homosexuals as helping with the family’s chores just so that more of their nieces and nephews can carry particular genes, as the article suggests. I think that most of us visualise homosexuals in more realistic environments, such as public bath houses, certain parks in your local town, or gay bars. There is ample research which informs about the outcomes of homosexuality, which appear to have little to do with adaptation and survival of human beings, and more to do with high risk behaviours, self-harm, harm to others - from a natural selection perspective, these are hardly desirable traits .

Personally, as I begin to understand it (albeit still in very basic terms), I find epigenetics to be exciting, because it explains the relationship between the DNA, its function in replicating life and particular characteristics, and the effects of environmental factors on this function. It’s also elegant; epigenesis involves what biologists refer to as ‘gene transcription’, which choreographs complex chemical interactions (e.g., methylation) at molecular level to determine biological outcomes without changes to the DNA.

Somewhere I’ve read a nice analogy, likening the DNA/genes and epigenesis to computer hardware and software, respectively. So DNA/genes are like the hardware – the computer. However, the computer cannot function without software; it needs an ‘operating system’. The DNA is like the hardware, whilst epigenesis is like the software . Epigenesis makes the genes function as instructed by the code inherent in the DNA … most of the time. Sometimes, however, you get a computer which does not function as intended. This was certainly true for me yesterday, when my PC at work would not read any of the USB sticks I stuck into it. I rung the IT people and, in true IT Crowd style, they took me through the ‘noob’ detection steps: 'turn the PC off and on; try the USB sticks in a colleague’s PC; check that you have the latest updates for Windows' ...

So where am I going with this? Well, I don’t need to be an IT person to understand that the PC was not functioning as intended. The IT Crowd at my work (I love them, actually, they’re so true to type, and fantastic people to boot) didn’t simply say “it’s normal, so get over it and accept it” – they came and fixed it.

Obviously, I am not saying that homosexuality should be ‘fixed’ in a similar manner as a computer might be fixed. I am certainly not in favour of electrocuting or sticking ice picks into people's frontal lobes to re-program them, whether they're manic depressive, homosexual, schizophrenics/shamans or witches. However, nothing takes away from the simple fact that, as I understand it, epigenesis is part of that genetic function which replicates life, and so it is part of the process that selectively employs genetic traits in a continuous drive to enhance the species' chances of adaptation and survival across generations. My understanding is that any other outcome is outside this blind function. Here is a somewhat lengthier quote, which merits close reading because it offers a clearer explanation of how certain traits can persist (bold type is for emphasis):

Within a population, beneficial alleles are typically maintained through positive natural selection, while alleles that compromise fitness are often removed via negative selection. Some detrimental alleles may remain, however, and a number of these alleles are associated with disease. Many common human diseases, such as asthma, cardiovascular disease, and various forms of cancer, are complex-in other words, they arise from the interaction between multiple alleles at different genetic loci with cues from the environment. Other diseases, which are significantly less prevalent, are inherited. For instance, phenylketonuria (PKU) was the first disease shown to have a recessive pattern of inheritance. Other conditions, like Huntington's disease, are associated with dominant alleles, while still other disorders are sex-linked-a concept that was first identified through studies involving mutations in the common fruit fly. Still other diseases, like Down syndrome, are linked to chromosomal aberrations that can be identified through cytogenetic techniques that examine chromosome structure and number.

(Source: Scitable)

So, I don’t understand how it should follow that homosexuality is not an aberration within evolutionary processes. Notice that I don’t hold that aberrations such as defective outcomes which lead to lessened chances of survival and to dead ends are not part and parcel of evolution. They are, indeed, characteristic of the evolutionary process, with a myriad examples of trial and error episodes in the drama and richness of life which have led to all sorts of mutations and failures – some more persistent than others, depending on environmental factors, among other things. However, I do hold that aberrations should be treated as such, and not represented as being ‘the normal’. Apart from ideological arguments, the proposition that homosexuality does not have deleterious effects for individuals and society is not sustainable in view of the evidence available. It is like arguing that people with manic depression are 'normal' simply because they are cognitively functional and 'no different' from anyone else. Nevertheless their moods and behaviour is affected in ways which affect their wellbeing and sometimes that of their loved ones, and the community's. No one is arguing that such individuals should be denigrated and discriminated against, but they need to be treated differently within the community so that the risks are minimised. For example, most life insurance will be more expensive for people with diagnosed manic depression. Yet this is acceptable, and such discrimination probably persists because people with this condition have not, unlike homosexuals, organised politically and through aggressive activism demanded of society that they be equated in all things in a manner that their condition and sexual preferences are never taken into account. This is a retrograde approach to dealing with disorders and abnormalities because they can impact on society. For example, in some non-Western societies, people with mental health issues are seen as 'useful' and normal, their disorders are channeled into particular social roles, like when schizophrenia is converted into shamanism. Anyway, scientific research has yet to find a gene for homosexuality, and until it does we have no option but to deduce that homosexuality is not an evolutionary improvement, in the sense that it enhances chances for adaptability and survival.

I found it interesting that Brooks did not pause over the fact that most epigenetics is focused on disorders, diseases and addictions. Epigenetics appears to be useful in explaining how random mutations and/or environmental factors influence, and sometimes lead to inter-generational transmission of harmful and undesirable physiological and psychiatric conditions (heritability). Indeed, respected scholars in this field tell us so: “Epigenetics can provide a new framework for the search of aetiological factors in complex traits and diseases” (Arturas Petronis, 2010, in Nature). So there is a wealth of epigenetics-focused literature on alcoholism, schizophrenia, drug addiction, depression, foetal syndrome, thalassemia, and so on and so forth. Curiously, Brook's article does not mention any of this literature, nor does it go anywhere near the proposition that homosexuality may not be what evolution ‘intended’. I am not sure that thalassemia, for instance, is a great evolutionary success seeing that it represents a failed adaptive response to mosquito-carried diseases in certain Mediterranean and Asian groups of people. Nor am I certain that it would be desirable to accept schizophrenia as 'normal', even though it has been around as long as same-sex behaviour. Even depression is viewed in epigenetics as something that should be accepted as a reality of human life, but which nevertheless ought to be treated as abnormal.

Since we would see it as normal to minimise the risks posed to society by schizophrenics, alcoholics, drug addicts and such, why have we come to treat homosexuality differently? Perhaps I am wrong, and I don’t sufficiently understand the science, and thus I am misinterpreting what it says. Nevertheless, I still perceive an interpretative bias in Brook’s short piece. This is very apparent in the following passages:

I found it interesting that Brooks did not pause over the fact that most epigenetics is focused on disorders, diseases and addictions. Epigenetics appears to be useful in explaining how random mutations and/or environmental factors influence, and sometimes lead to inter-generational transmission of harmful and undesirable physiological and psychiatric conditions (heritability). Indeed, respected scholars in this field tell us so: “Epigenetics can provide a new framework for the search of aetiological factors in complex traits and diseases” (Arturas Petronis, 2010, in Nature). So there is a wealth of epigenetics-focused literature on alcoholism, schizophrenia, drug addiction, depression, foetal syndrome, thalassemia, and so on and so forth. Curiously, Brook's article does not mention any of this literature, nor does it go anywhere near the proposition that homosexuality may not be what evolution ‘intended’. I am not sure that thalassemia, for instance, is a great evolutionary success seeing that it represents a failed adaptive response to mosquito-carried diseases in certain Mediterranean and Asian groups of people. Nor am I certain that it would be desirable to accept schizophrenia as 'normal', even though it has been around as long as same-sex behaviour. Even depression is viewed in epigenetics as something that should be accepted as a reality of human life, but which nevertheless ought to be treated as abnormal.

Since we would see it as normal to minimise the risks posed to society by schizophrenics, alcoholics, drug addicts and such, why have we come to treat homosexuality differently? Perhaps I am wrong, and I don’t sufficiently understand the science, and thus I am misinterpreting what it says. Nevertheless, I still perceive an interpretative bias in Brook’s short piece. This is very apparent in the following passages:

The idea that “gay people don’t have children” is simplistic and, historically, wrong. Being gay does not necessarily mean not having a family, and throughout history many – perhaps most – homosexuals spent time in heterosexual unions, having children. And yet even if a small proportion did not, this could have exerted strong evolutionary selection against any genes involved. ... But perhaps those genes provided some other kind of evolutionary advantage that outweighed the direct cost of having fewer kids

Brooks' paper does one specific thing here, it leaves out from what it emphasises one significant and very relevant objective fact. That is, same-sex copulation cannot produce a natural family. This requires coitus, sex between a male and female. Two men or two women cannot produce offspring naturally. Certainly, this fact is implied, but is not emphasised, nor are other implicit interpretations ridiculed in the same way. The paper does not say, "The idea that two people of the same sex can have children and form a natural family is wrong". The reason for pointing this out is to highlight the manner in which truisms are created in scientistic explanations. Such explanations tend to leave out or marginalise objective facts which are likely to be pointed out in alternative arguments in the political debate within which the practitioner of scientism situates themselves.

Apart from a few extremists, not many (especially among the Conversation’s readership) would seriously think that homosexuals are incapable of having children or establishing families. William Shakespeare is a famous example, so was John Maynard Keynes (though he could not produce children because of medical problems), as was Alfred Kinsey; Brooks would surely be familiar with Kinsey's work especially as he is dutifully mentioned in the paper he quotes. Yet Brooks' paper incorporates this truism, just as it incorporates inflated claims - for instance that the homosexuals represent a 'large' proportion of the population. Why so? [Update: And why does he get so angry and labels my writings as barely concealed homophobic and bigoted ideas, instead of clarifying the point?].

(Incidentally, Shakespeare and Keynes accepted who they were and lived and contributed to society as best they could [can't do much better than giving us Shakespearean literature + 1000 or so English words; and macroeconomics!], but without trying to overthrow its institutions just so they can fulfill their sexual drives. On the other hand, Kinsey did his best to do just that, and in the course of this initiated the sexual revolution).

Forgive me, dear readers, but I would rather believe in the magic of Santa Claus than in scientistic explanations which imply that homosexuality leads to advantageous evolutionary outcomes. I find the former an affirmation of the human spirit, and the latter an insidious subversion of it.

Recommended: Petronis, A. (2010). Epigenetics as a unifying principle in the aetiology of complex traits and diseases. NATURE. 465(10): 721-727.

Apart from a few extremists, not many (especially among the Conversation’s readership) would seriously think that homosexuals are incapable of having children or establishing families. William Shakespeare is a famous example, so was John Maynard Keynes (though he could not produce children because of medical problems), as was Alfred Kinsey; Brooks would surely be familiar with Kinsey's work especially as he is dutifully mentioned in the paper he quotes. Yet Brooks' paper incorporates this truism, just as it incorporates inflated claims - for instance that the homosexuals represent a 'large' proportion of the population. Why so? [Update: And why does he get so angry and labels my writings as barely concealed homophobic and bigoted ideas, instead of clarifying the point?].

(Incidentally, Shakespeare and Keynes accepted who they were and lived and contributed to society as best they could [can't do much better than giving us Shakespearean literature + 1000 or so English words; and macroeconomics!], but without trying to overthrow its institutions just so they can fulfill their sexual drives. On the other hand, Kinsey did his best to do just that, and in the course of this initiated the sexual revolution).

Forgive me, dear readers, but I would rather believe in the magic of Santa Claus than in scientistic explanations which imply that homosexuality leads to advantageous evolutionary outcomes. I find the former an affirmation of the human spirit, and the latter an insidious subversion of it.

Recommended: Petronis, A. (2010). Epigenetics as a unifying principle in the aetiology of complex traits and diseases. NATURE. 465(10): 721-727.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed